The Washington Post Has a Taylor Lorenz Problem

Lorenz has been central to the media's anti-tech campaign.

It’s been a busy weekend for the Washington Post, which endured internecine fighting that makes Russian-Ukraine vitriol look comparatively meek. Post reporter Dave Weigel retweeted a crass joke, prompting the wrath of another WaPo reporter, Felicia Sonmez, which then prompted a backlash by yet another Washington Post reporter, Jose Del Real, who accused Sonmez of cruelty, who then accused Del Real of…I’m actually not sure of what.

If this has you rolling your eyes, either in disbelief at the juvenility or in confusion, that’s a good thing. It means that despite the Twitterverse’s best efforts you’re still fairly sane. But amid the melee, another scandal hit the Post, this one much more serious.

Taylor Lorenz, the Post’s “technology and online culture” columnist who formerly worked for the Times, wrote a column about YouTubers who covered the Jonny Depp-Amber Heard trial. In her column, Lorenz provided quotes from two YouTubers at the center of the story, who later said they’d never been interviewed by Lorenz. Those offending quotes were then stealth-edited out the piece. The Post was forced to issue a lengthy “Editor’s Note,” a move no reporter, or editor, relishes.

If Lorenz made up quotes attributed not just to sources but subjects of a column, that puts her squarely in Blair-Glass territory. That’s a dangerous place to be. It’s pretty much as serious as it gets. But it’s also nothing new for Lorenz.

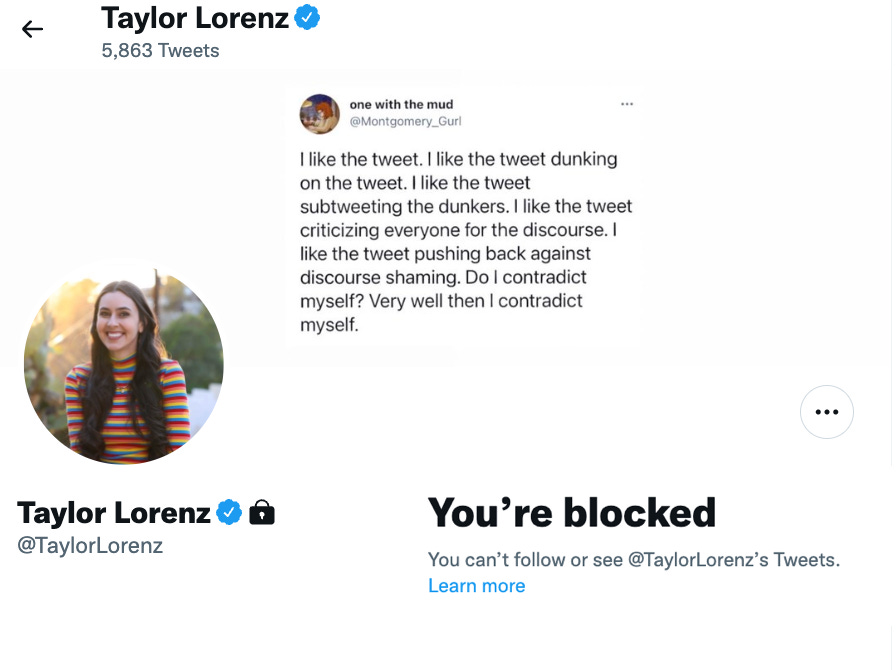

(For the record, Lorenz has blocked me on Twitter.)

If you recall, Jayson Blair was the rising young star reporter at the New York Times who fabricated not just quotes but entire stories about veterans of the Iraq War coming home broken. Blair was filing multiple articles a week on this larger subject, while still covering the DC Sniper Case. Putting aside the Herculean journalistic output this would have required, the physical logistics of Blair’s travel would simply have been impossible.

Stephen Glass provides a similar case study in malfeasance. Glass admitted to fabricating articles in the New Republic that targeted organizations, including drug abuse organization D.A.R.E. and the College Republican National Committee, that offended the ideological assumptions of the New Republic and its readership.

What’s key to understand here is not just that the targets motivated the targeting. It’s that they made beyond-belief reporting very easy for their respective news organizations to believe.

This kind of purchased credulity revealed the real rot at the heart of the news organizations, which are designed to weed out falsehood. And with Blair, at least, the purchased credulity succeeded despite the efforts of multiple editors who’d flagged his reporting, which included wild errors, including in spelling and grammar.

The reason was that the story Blair was telling was just too good. It confirmed too many of the assumptions made by the masthead and publisher of the paper. As I show in The Gray Lady Winked, my book on the Times’ misreporting, it did too much good work, “important work,” especially in the wake of the Times’ WMD scandal in which the paper appeared to serve as a cheerleader to Bush Administration claims, to be faulted without drawing unwelcome attention to the whistleblower.

For the past decade, the traditional media has waged virtual war on its greatest rival for power and influence in American public life—tech. Almost every social ill has been laid at the doorstep of the tech industry, by the media. The public has been exposed to an endless tech diatribe about how tech has weaponized content in order to monetize clicks and likes.

The irony here is palpable, given that not only has the legacy media been doing this since the “Yellow Journalism” days of Joseph Pulitzer, but produced the grist for the algorithmic mill in the form of news content.

Lorenz has been central to the anti-tech effort, taking on major figures from tech, in some cases through false allegations, such as claiming Marc Andreessen of Andreessen Horowitz used the epithet “ret*rd” in a Clubhouse discussion. More recently, Lorenz was accused of doxxing the conservative Twitter user Libs of TikTok as part of an in-depth investigative piece that revealed the user’s identity and linked to a document that showed her home address.

Influencer innovator Ariadna Jacob has gone so far as to sue Lorenz and the New York Times for what she claims was a hit piece so riddled with falsehood that the piece barely stands up to scrutiny. Nevertheless, Jacobs’ says her business was eviscerated overnight. And that’s the point: the allegations don’t need to be true in order to stick.

This is the core tactic used by political muckraking—make an accusation, make it extreme, make it big and, if it’s challenged strongly enough, quietly retract it. It’s now often the media’s fighting style of choice, what I’ve previously identified at the “Knee Cap Media,” which has shot up in prominence over the past few years.

Although it’s effective, things go really wrong when reporters start getting caught making stuff up. To many observers, especially on twitter, this seems to be where Lorenz is headed. Just like Glass and Blair, Lorenz is a young, bright reporter with a rocketing rise to the top. But there is very much an Icarus lesson here to be learned.

While the partisan media landscape might serve as super-glue to Lorenz’s journalistic wings, the political sun is still blazing hot and professional gravity just as fierce as it ever was.