Was Kanye destroyed by Ye?

When the persona becomes the man, things go horribly wrong.

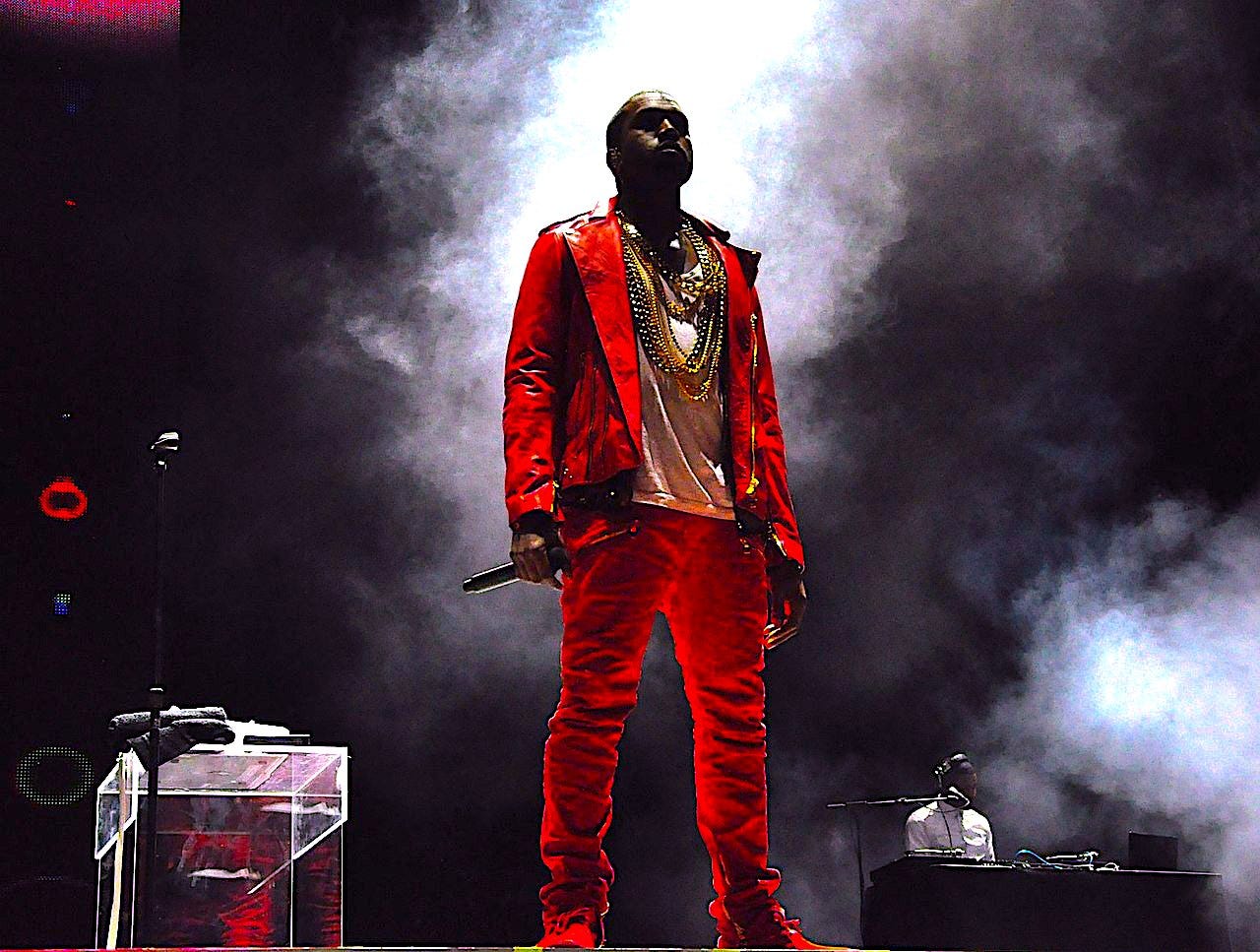

Image: CC BY-SA 2.0 license

I’m not a big fan of hip hop, but I love Kanye West. I grew up in Southern California in the 1990s when hip-hop was in its golden era and it was everywhere. For me, it never really clicked, though for all my friends it did. I preferred punk and classical (a weird mix, I know).

But Kanye West changed that. His first album, College Dropout, was like nothing I’d ever heard, not merely in the context of hip-hop or rap but in any genre of music. It was glorious, rude, artistically brilliant, inspiring, confounding, and thematically all of a piece. It derided higher education, something I then cherished, but in doing so convinced me (at least in part) that Kanye was right about it. It wasn’t a “critique.” It was a celebration of scorn for the fake exclusivity peddled by our university system. It was the kind of thing you find in great literature.

In the past few years, I evolved from a Kanye fan into a Kanye obsessive. I’ve cycled through his albums, listening to the same album for months on end every day, almost to the exclusion of other music. Right now, it’s Late Registration, which includes a track called “Gone” that awes me each time. Before, it was Life of Pablo. Before that, Graduation—though I always return to Dropout. I’ve written books while listening to Kanye. I’ve changed my life while listening to Kanye.

So it was natural that the recent uproar over statements tweets made by Ye (the latest incarnation of Kanye’s public persona) concerning Jews gave me pause. Despite tongue-tied attempts to defend or defang them, Kanye’s tweets are, on the face of it and by any reasonable interpretation, anti-semitic. You don’t pledge to go “deathcon 3 on Jewish people” without importing some serious anti-Jewish sentiment—or, put more directly and simply, Jew-hatred—into the picture. The question is why he said it, why he did it?

The first and move obvious response is mental illness. Kanye has spoken publicly about his struggle with bipolar disorder. You can see the manifestation of his disease in living color in jeen-yuhs, the Netflix multi-part documentary on Kanye made up of footage shot in real-time by one of Kanye’s oldest friends.

In one scene, Kanye meets with a pair of investors, one of whom is the legendary Mike Novogratz. It’s painful to watch. Kanye, wearing a camouflage weight vest, babbles incoherently while the investors look on, pretending to understand. Perhaps they were only attempting to commiserate, the way you do with a mentally ill person on the street approaches you with something very important to tell you, they just don’t know exactly what. So you listen, to at least afford them the dignity of seeming to be heard.

In this regard, it’s interesting that Kanye has adopted the aesthetic of the street—not the capital-S-street of urban style, but the lowercase of trash bags worn as clothes and tents pitched beneath highway overpasses. Even in his recent Tucker Carlson interview, which, it was later revealed, also included barbs and jibes slung at Jews that were edited out of the piece, Kanye carried that aesthetic, with clothes that look found and a beard that did not look thick by choice.

In this, Kanye has identified a hidden, radiating core of our culture. Homelessness is phenomenon that has risen in America on a scale that is hard to understand. In the big cities, in the suburbs, in the towns—it’s there: an accusation, an indictment of a failing society. We want to ignore it, pretend it has nothing to do with us individually, or tuck it into the fold of politics by blaming it on our political adversaries. Kanye put it on the catwalk, on the cover of magazines, and all over social media.

Brilliant artists often bring their creations into the world. But artistic geniuses bring the world into their creation. Kanye has brought us into the world of the shattered, dissembled street. But in doing so, he has turned that street into his life—complete with the street corner mutterings and ramblings about all the usual suspects: Jews notably among them, but the corporate string-pullers, the government, his ex-wife, and a cadre of anonymous tormentors persecuting his existence included as well.

Does this make Kanye’s anti-semitism more palatable? Or even more understandable? Would any reasonable person report the ramblings of a homeless mentally ill person as a hate crime? I wouldn’t. But what does that mean for a self-described “multi-billionaire” who, no doubt, has the financial resources needed to get help?

Beyond anti-semitism, there is also a conversation lurking here about mental illness. Anyone who’s come close to it knows that one of the symptoms is the refusal to get help. Psychiatric or psychological assistance is alternately cast as unnecessary, diabolical, harmful or ineffective. America is facing a mental health crisis that we have not addressed. It will only get worse.

But what if, for a moment, we factor out the mental illness and consider only the artistic genius, the genre-maker, uttering these words of hate: is their effect ameliorated or exacerbated? I think about genius Jew-haters whose work I love or admire—Roald Dahl (whose books I read to my children), Coco Chanel, Patricia Highsmith, Wagner, T.S. Elliot, Henry Ford, or Charles Lindbergh. What about Heidegger, who mortgaged his integrity to the Nazis? Are we to discard or discredit their work because of the ugliness of their hatred? Should Jews and anti-racist advocates tear down their statues, burn their books, and destroy their creations?

My favorite word in the English is also among the simplest: and. It’s a strange choice for a writer, certainly no “cellar door,” but it prompts the most revealing questions and force us into spaces we otherwise believe we cannot fit. Can we condemn Kanye for his terrible statements and love his music? Can we pity and admire him? Can we hold him completely accountable and provide him enough leeway to try understand him?

Human nature bends towards dichotomy. As with all things, America has super-sized that inclination. It only permits black and white. This is an idea Kanye, just days before his anti-semitism scandal erupted, capitalized on with his lethally divisive “White Lives Matter” stunt, which had him and Candace Owens decked out in black (for Kanye) and white (for Owens) t-shirts carrying that slogan.

In this, Kanye touched America’s dichotomous nerve. America thrives on the “either-or” of judgment and loathes the “and,” which is the conjunction of compromise—and of contradiction. It’s the artist’s contradiction, while either-or belongs to the politician. Like any great artist, Kanye is able to fill the space opened by the and. He has learned to dance in that space, supported by the tension it creates .

The problem is when the work and hateful sentiment or immoral idea collide. You don’t have to listen to Kanye long or hard (certainly not as long and hard as I have) to hear the shocking anti-Jewish lyrics in his music. As I write these words, a track on a Kanye album is telling me that “Black on black lies is worse than black on black crime/ The Jews share their truth on how to make a dime.”

Which brings us to the other unavoidable but so long avoided point—the specter of anti-semitism in hip hop. Some writers have tackled it as a subject but American culture, so busy scrubbing every whiteness off every surface, has somehow missed this very prominent, very ugly blemish. You can hear it in Kanye, you can hear it in his one-time mentor Jay Z. You can hear it almost everywhere that hip-hop is.

Can it be that our cultural silence on hip-hop’s Jewish problem, especially in the context of our wild embrace of the art form, has not just excused it but validated it? Is it possible that we are as much to blame as Kanye for the remarks he made (the and at work again)? After all, if we condone anti-semitism in his music, why should we condemn it in his tweet?

I often watch as brave people attempt to present a rational understanding of the scourge of anti-semitism. What is it? Where does it come from? Why is it? There is no answer. There is only this strange phenomenon that has accompanied human experience whenever and wherever there have been Jews—and frequently, where and when there have not been Jews (a phenomenon Joyce pointed to in Ulysses when the headmaster of the school Stephen Dedalus works at asks rhetorically why Ireland is the only country that never persecuted the Jews: “Because she never let them in.”).

For Kanye, you can’t help think that the man—the artist portrayed so beautifully in the Netflix documentary as a young, brilliant, generous and, above all, earnest creator—has slipped into the vortex of a celebrity persona, the Ye of his own creating, and may not be coming back.

This was only reinforced in the most recent flare-up of his recurring rash of anti-Semitism when Ye insisted on air with Chris Cuomo that NewsNation change the chyron from “Kanye West” to “Ye.” De-misnomered, Ye went onto to spew more anti-Semitic hatred, accusing Jews of running Hollywood.

But perhaps there is a turning point here, and perhaps we can throw this man a three-lettered life-line, affirming he can be wrong and, maybe because of his wrong, he can also seek and find redemption.